The punchline first: SolarList is basically closing. We haven’t been actively operating the core business since the end of 2013. The founders are currently working on other projects. We spent most of 2014 trying to find a suitable partner

for the business and software, but we currently do not see a way forward. We would still love to find someone to work with to help more people go solar. As you’ll see from the rest of the post, we still fundamentally think it’s a great idea. But the fact for now is we’re closing up shop.

What’s next

We have built a ton of cool software and learned a lot about finding, educating and turning homeowners into happy solar customers. If you are interested to work with us, license our technology or have a compelling non-profit use case. Please give us a shout.

The story

SolarList encompasses a three year saga of failures and hard-won triumphs. There’s another blog post coming attempting to glean some generalized lessons from the story, but I wanted to put the full gory narrative out there for the cleantech community and for aspiring entrepreneurs. Hope you find it more useful than tedious.

Origins

Before SolarList, I worked at a cleantech consulting startup called New Energy Finance, since acquired by Bloomberg LP. One of my main roles was producing the Levelised Cost of Energy Quarterly Outlook. The goal of this paper was to examine the apples-to-apples to cost of all renewable and non-renewable forms of electricity generation across every market and every geography. Since the nascence of renewable energy in the 1970s the single dominant problem for the entire industry was that the cost of the equipment (solar panels, wind turbines, electric batteries) needed to come down. As I tracked these numbers quarter by quarter, it became clear in 2008 that many technologies in many markets were approaching an inflection point where they would be become broadly cost-competitive with traditional electricity. All the industry’s brainpower, all the venture capital and all the entrepreneurs were still investing time and energy in incremental improvements to the capital cost of equipment, meanwhile manufacturers of the dominant variants of solar panels and wind turbines reached critical mass.

There was a bloodbath of startups and investors who bet on new technologies to reduce the cost of equipment. At the same time almost nobody was looking at how the industry would scale up. How would it develop 10x or 100x more projects, how would it market and acquire 1,000x new retail customers. The best project developers still didn’t have basic CRMs or any process automation. Marketers of solar panels and other retail products had not innovated beyond plowing huge sums of money on Adwords, driving up cost per click to soaring heights, or paper door hangers. Meanwhile, nobody, almost literally zero people, in the entire industry had any competency in web scale software development. As the cost of equipment fell, soft costs like sales and marketing and customer acquisition composed a greater share of final consumer cost. I saw the opportunity and quit my job with the vague aim of building software to attack these soft costs with automation, simplicity and education.

It’s worth pointing out here that at this point, beyond reading the Rails Tutorial book, I too knew basically nothing about software development. But I had that special blend of overconfidence and ignorance that makes twenty-somethings want to start a company and disrupt an industry.

Failing to launch, then failing again

With a crisp copy of The Lean Startup on my desk I set about interviewing everyone remotely associated with the industry, doing “customer development” in Lean parlance. I had dozens of interviews with project developers, consultants, homeowners, friends, facilities managers and random people surveyed via Mechanical Turk. It became clear that this overall problem, inefficiencies in scaling and soft costs, was most acute in the residential (home) solar industry. What was needed was an easy to use website that let people who were interested in solar educate themselves about the costs and benefits and options. They would self-identify as interested in solar and the app would then connect them with best solar companies. Something vaguely like a Craigslist for solar: hence SolarList. At the time it was not crazy for solar companies to spend $5,000 – $10,000 per customer purely on sales and marketing costs so this matchmaking would be exceptionally valuable.

So the next step was obvious, another friend in the industry, who also knew nothing about software, and I would go hit up some angel investors, raise some money, hire a developer to build the first version of our product, one or two more steps, and we would revolutionize the solar market! I continued to do customer interviews, gather data, create and tweak Powerpoint decks. And we did a lot of pitching. At this point it should be obvious to most that we were not super successful with this strategy. A decade ago it was possible to raise money as two non-technical people with a software idea. But for most people who aren’t incredibly connected within the Silicon Valley scene, this is a fool’s errand. However, through shear brilliance of my then-co-founder we did actually get a term sheet for $100k from one angel investor. Fortunately I had been consuming books — highly recommend this one — and blog posts on venture term sheets non-stop for a month and saw that the document was so riddled with every horrible term sheet trickery that it would be better not to build the company at all than to do so with this as the foundation.

We killed the idea and the strategy of trying to get angel money in pre-product. We then spent several months exploring partnerships with app development shops. The problem with these deals is that you as the entrepreneur bring just the idea to the table and really have no leverage. Several months of work later we scrapped any version of this strategy. It became clear that SolarList needed an individual technical co-founder to move forward. It was also clear that the current team wasn’t a good fit for that strategy. There was a series of awkward conversations, several things left unsaid that should have been. I’m still not happy with myself about how it all went down but SolarList lost one co-founder before there was even a glimmer of forward motion.

Bootstrapping is hard

At this point I am about nine months out of a job and completely back to square one. I was still living in NYC at the time and I began networking furiously in my hunt for a technical co-founder. I went to every Meetup, mini-conference and hackathon I could. From the very beginning I believed that I needed to learn enough to be dangerous about web development and had been studying hard. By this point I was a founder with a good idea, industry expertise, and, critically, some basic coding skills. With this song and dance I was able to attract a decent number of interested developers and eventually found Matt, an insanely talented Ruby developer with experience working in the solar industry. On paper we were the perfect combination. We had a few discussion and quickly agreed on a shared IP agreement to get to work on a prototype. He lived out of town so, about two weeks after meeting, he moved in to my apartment, sleeping on the couch for a week while we coded 16 hours a day.

From a technical standpoint we started with a hugely ambitious goal for the software. We wanted to completely automate the entire customer acquisition process, building a web app that would generate a complete solar quote and financing package for any home in the US without any interaction with sleazy sales guys who we assumed were a big part of the very high cost of customer acquisition (We later leanred a great deal of respect for those sales guys). After a week of non-stop coding we actually had a pretty decent proof of concept and a good idea of what else we needed to build. But we had a big problem. Both us of were pretty much broke. To get our plan off the ground we needed time to finish the product, launch it and ramp up monetization. I sublet my apartment to cut rent from my cash burn, put my laptop in a backpack and flew to Spain (on miles), lived in hostels and Airbnb (charged to credit cards) and worked every day from cafés. We kept pushing the product forward but struggled with remote collaboration. We spent a painful amount of time entering app competitions and applying for grants to no avail. We launched a version of the product but couldn’t afford any marketing to drive traffic to it. We felt we urgently needed a seed investment to get SolarList jumpstarted.

A big solar company was sponsoring a Cleanweb (cleantech + web software) hackathon in San Francisco. It was so up our alley that we both bought one-way tickets with the intention of winning the hackathon and parlaying that into an angel investment to launch the company. We arrived at the hackathon and pitched our idea to the developers, designers and marketers in the crowd. At that point Matt and I had a clear and compelling understanding of our market, and a foundational product already built. So we easily attracted the all-stars in attendance, including a hackathon legend. We easily won the top prize ($2,000 + a free consultation and incorporation from a top Silicon Valley law firm). So far so good. The next step was an SF road show and an angel investment. We hammered absolutely everyone we knew for intros and pitched everyone who would listen. We spent a month in San Francisco. Crashing everywhere from friends’ couches, hotels in sketchy neighborhoods (booked with miles) to the even sketchier Startup House, a horrible hostel for SF’s legions of broke bootstrapping founders.

Here we learned a hard fact that haunted SolarList from day one. There were, and still are, exactly zero investors interested in early stage cleantech companies. When we first started out, two funds, Sunil Paul’s Spring Ventures and the incubator Greenstart, were making angel investments in cleanweb companies but by they time we got there, both had moved elsewhere. Beyond that, every investor had heard nothing but horror stories from big shot VCs getting hit with $100 million write-offs in the cleantech sector. Never mind that those investments were in massive factories and physical products while we were a lean consumer web company. Funds had been burned or seen their colleagues get crushed in cleantech and they were having none of it. Of course they didn’t come out and say that. We had brief meetings and pitched a ton of investors, because investors like to take meetings and hear pitches. And of course we never got an explicit “No” because investors like to keep their options open and see if anybody will be a first-mover, but none of the conversations ever went anywhere.

Burning through money, not making progress on fundraising, we began to fight about how to code our way out of this corner. I was convinced the only way to make meaningful revenues was to convert our product to a B2B SaaS service and sell it to solar companies. Eventually we stalemated on product development. Making no progress on any fronts our only option was to part ways. I am really sorry that this partnership didn’t work out and tons of lessons were learned, most importantly that startups are freaking hard.

Going it alone

Matt was a much better developer than I was so the code base we had built together was way over my head and I had to scrap it. It’s about 14 months since I quit and I’m back to square one again. A good friend, Sustainable John, offered to let me crash his place in Berkeley while he was out of the country for a month. Despite making lots of technical progress, Matt and I had never launched a fully working product that could truly make money, so I decided it was now or never. I had been sharpening my coding skills for over a year while failing three times to solve the problem of how to really build the app. I thought, what the hell, I’ll try to build it on my own. I gave myself 10 days to build a working product that I could sell to solar companies or I would quit the whole thing. I finished in 8 days, bleary-eyed and jittery from too much coffee and a lack of sunlight and exercise but with a working, sellable product.

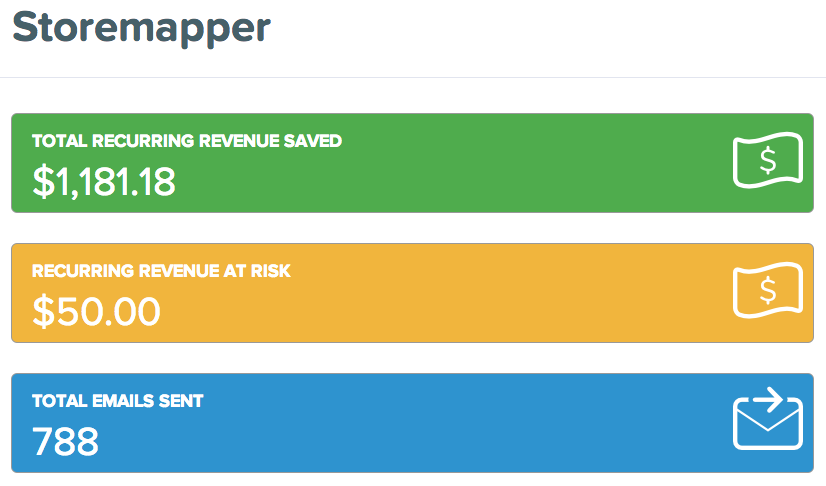

I started the slow process of pitching solar companies on my B2B software solution. I put every company in my personal network plus the entire member list of the Solar Energy Industry Association in a lead list and started with A. In short order my time in Berkeley was up and I needed a super low cost place to hang out and continue emailing and cold-calling. South America looked good and cheap and there was a pretty girl I could meet up with there. I hopped a flight to Buenos Aires (I had a lot of frequent flyer miles at the time) and set up shop. It was on this flight that I built Storemapper, the only product I have launched that actually got some traction.

About 400 sales pitches later it was clear I was off track. The very reason I felt there was an opportunity in the market, that the industry didn’t have anybody who understoond the value of web software, meant that none of the companies I was pitching had anybody on staff who could be the internal champion for the product. A few companies, like Clean Power Finance, succeeded in selling software to this market primarily because the software so obviously worked and added value by automating repetitive tasks done on paper, but selling software to solar companies has so far proven to be a tough model. The current iteration of SolarList required that companies make a small bet (the price of SaaS) that the app would lead to more higher quality leads and in turn more revenues. I got the same answer over and over again: “Bring us warm leads and we’ll buy them all day long but we don’t to pay for lead generation tools.” If you’re losing count this is the fourth attempt with more or less nothing to show for it.

A new hope

While still in South America (Peru at this point) it became increasingly clear that SolarList version 4 was not going anywhere. I started to spend more of my time on other projects, freelance software development, ecommerce consulting and other side projects. I had this big lesson learned from discussions with solar companies, they wanted sales leads, tons of them, and were willing to pay big bucks for them, but I didn’t have a clear path to generating my own leads and I was losing a little steam to keep pressing forward. Around that time my friend and former co-worker, Michael Conti, pitched me on an idea: Cutco for solar. We would train legions of students to educate homeowners and create warm leads that we would pass on to vetted solar companies for a fee. The idea was a perfect fit. It matched with everything I had learned to date and was a clever way to generate our own leads and quickly generate revenue. Michael was not only very well-connected in the solar industry, but also a master large-scale organizer. The perfect co-founder to recruit, train and motivate hundreds of college students to go bang on doors. We agreed immediately to join forces. Shortly thereafter, Sustainable John joined us an advisor and practically a co-founder, given how much work he put in, giving us a West Coast presence and serious eco-rapping street cred.

Great progress and a big mistake

In January of 2013 I moved back to New York City. Michael and I started work on this new version of SolarList. But I had a huge problem. I had barely been able to scrap together the cash for first month, last month and deposit for a room in an apartment in Brooklyn. I was a good enough developer at this point to charge a decent per hour rate for freelance work but I didn’t have enough clients to earn enough to afford the NYC cost of living. It was a full-time job finding clients and freelancing enough just to do work enough to afford the City, leaving little time and bandwidth left over to do hard startup things. Taking on this extra overhead without savings or passive income was the single biggest mistake I made through this whole process as it meant we either needed to quickly start generating at least $10k/month in profits or we needed to raise money just to cover our cost of living.

Trading off time with paid work, we didn’t finish retooling the product and recruiting students for our first beta test until May 2013. In early Summer we did roll out beta tests on several campuses. Dozens of totally awesome students came out, volunteering for free, to canvas their cities and test our new solar assessment mobile app. The results were fantastic. Students were able to provide accurate solar assessments and educate and qualify potential customers without any real training using our software. Theses warm leads were stored in our app’s database where we could route them via email to solar company customers. We sold some leads and gave some away to companies to get feedback on whether or not they were valuable (they were). The students were excited and felt empowered to actually effect change in their community. And all the numbers worked. We had a detailed understanding of the solar sales funnel by this point and it was clear that this method would generate new customers at a much lower cost than best in the market.

First money in

We felt we had the data we needed to go full-time. After wasting nearly a month of work applying to the Department of Energy’s Sunshot program for a $500k grant (complete waste of time) we finally caught a break. We entered SolarList in the NYC Big Apps competition. The contest had a cleantech category which we won, earning us $20,000 and the help of the city Economic Development Commission with introduction to VCs. For all my previous complaining about the high cost of NYC, it’s worth noting that without this catalyst, SolarList probably would have fizzled again at this point. Looking to capitalize on the momentum we fired up another fundraising process.

We were looking for $500k to make a few hires and fund working capital as our business still had a long sales cycle between when a student would canvas a home and when we collected from the solar companies. We wanted to scale up the students rapidly and still be able to pay them in a timely fashion. If we were aggressive in fundraising the first time around, this time we were ferocious. We pitched hundreds of investors, cold-calling and emailing basically every early stage investor and fund in the country. Michael called in every favor he could, I interrupted a date night to cold intro myself to Dave McClure at the bar in Birreria. We hammered phones and emails and got conversations with almost everyone on our list eventually even getting a final round interview at Y Combinator. But we were still beating our heads against the wall. There was money for mature cleantech companies, but absolutely nobody wanted to put early stage money into the cleantech market. We had a functioning product with operating data, an all-star team and we understood the market better than anyone, but we got basically nowhere. We closed $135k from friends and a family office, to whom we are immensely grateful, but after several months we decided it was best to do what we could with money rather than keep fundraising.

$155k wasn’t nearly the capital and runway we needed to execute our original plan so we had to make a choice to focus on one part of the sales funnel. We didn’t have the time or bandwidth generate lot of leads, sell them to lots of solar companies and make sure all of them converted to actual solar sales, so we decided to focusing on showing that we could scale up the lead generation. There was tons of good data on how much leads could be sold for at volume and what percentage would convert to new customers. We hoped to get data showing we could generate X leads and raise more money based on the premise that X leads would be worth Y dollars if we had time to do the biz dev and sell them. It should be obvious by now that one of our biggest problems was being fundamentally dependent on the possibility of raising money and assuming “if we get to this next milestone, then we’ll be able to raise money and do things right.” We never focused on actually bringing dollars in the door because we assumed that investors would be able to make the extrapolation from leads to dollars if given copious data on average price per lead. This was an incorrect assumption.

Michael, John and our truly amazing interns devised and executed a plan in three weeks to launch The Solar Bowl with over a dozen college campuses across the country competing to educate the most homeowners about their solar potential. More than a hundred students signed up and used the app to create a solar assessment and hundreds of homeowners were qualified with about 300 solar leads created in less than six weeks. The software worked. Nearly all the students were able to easily give accurate solar assessments to homeowners with no training. Theoretically that would have meant about $15,000 – 30,000 in revenue at that time but the leads came from all over the country and we hadn’t had the bandwidth to vet companies and set up lead generation agreements with enough companies to monetize them effectively. The data however was very compelling. Students were fired up and it was clear we could scale the operation to 1,000s of students without hiring much more staff. On top of that the total cost of customer acquisition was dramatically lower than anything else in an industry very hungry for more customer growth.

Go big or go home

At this point we had a choice. We could more or less could see that this could be a business that would work. If we continued to grind it out we could slowly grow the number of Solarists (as we called our amazing canvassers) generate lead generation revenues and eventually build something big. But we had two problems. First, while I have tremendous respect for folks who have been out there putting solar on people’s roofs for 20 years, the customer service for many of the companies in this space was terrible. After handing off customers to these companies we found it could be nine months or more before they finally got solar on their roof. The processes were slow, inefficient and painful for the customer. We knew that we wanted to own that entire process, fully walking the customer all the way down the road to the end. But that meant hiring sales staff as there was no way the two founders could handle the sales process and manage the rest of the business. Secondly, call it what you will, but Michael didn’t want to build a tiny solar sales company and spend 5 years growing it organically. We wanted to make a big serious impact on the industry, otherwise it wasn’t worth it for us.

We agreed easily that we had to go big or go home. We had years of customer and product development, deep industry insight, demonstrable data that the we had a truly innovative and much more effective way to scale up the industry. We pulled out all the stops for a hail mary fundraising attempt. Eventually we widened our search to other solar companies, strategic partnerships and would-be competitors to try to somewhere acquire the capital to get the business to scale. But one by one we checked every one we could think of off the list and ran out of ideas. We also ran out of money. By March of this year we both had to go back to other work to pay the bills.

We spent the rest of the year looking for ways to partner with big companies in the industry to revitalize the Solarist program but at this point we just haven’t found a good fit. We have a few ideas incubating for re-launching the product but for now it’s on the shelf.

Gratitude

I (Tyler) have told this story as a first person narrative so it comes across as very me-centric. But that’s not how it really played out day to day. I could not have made any of the progress without help from co-founders, friends, investors, supporters and colleagues who helped immeasurably at every step of the way.

Several people took big gambles with their time and careers to join SolarList as co-founders. They worked their butts off and didn’t see a pay-off. Within the cleantech industry we had tons of helpful cheerleaders who made introductions and provided helpful advice. Our friends and colleagues were insanely supportive and helpful in the day to day and several of them took even bigger risks, investing some of their savings in Michael and myself. We are supremely grateful. I’m hopeful that our experience so far is useful for aspiring entrepreneurs and I’m even more optimistic about the future potential for solar and cleantech.

Thanks for the journey and for reading.